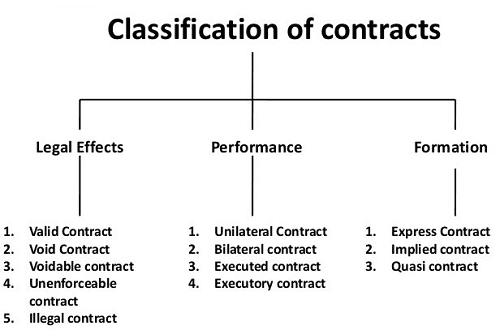

Classification of contract- Contracts can be classified in various ways based on different criteria. Here are some common classifications:

1. Classification Based on Formation

- Bilateral Contracts: Both parties make promises to each other. Example: Buying goods from a shop.

- Unilateral Contracts: Only one party makes a promise in exchange for an act. Example: A reward offer for finding a lost pet.

2. Classification Based on Performance

- Executed Contracts: Both parties have fulfilled their obligations. Example: A contract where goods are delivered and payment is made immediately.

- Executory Contracts: Some or all obligations are yet to be performed. Example: A contract for a future sale of goods.

3. Classification Based on Validity

- Valid Contracts: Legally enforceable, all essential elements are present (agreement, consideration, capacity, etc.).

- Void Contracts: Lacks one or more essential elements, thus unenforceable. Example: A contract for illegal activities.

- Voidable Contracts: One party has the right to void the contract (due to factors like coercion, fraud, etc.).

- Illegal Contracts: Contracts that involve unlawful acts and are unenforceable.

4. Classification Based on Enforceability

- Express Contracts: Terms are stated explicitly (either orally or in writing).

- Implied Contracts: Terms are inferred from the conduct or circumstances of the parties. Example: A service contract when you ask for and pay for services.

- Quasi-Contracts: Imposed by courts to prevent unjust enrichment, even though no actual agreement exists.

5. Classification Based on the Nature of the Consideration

- Contract of Sale: Involves the transfer of ownership of goods in exchange for money.

- Contract of Services: Involves the performance of services in exchange for payment.

These classifications help determine the legal rights and obligations of the parties involved in the contract.

What is Required Classification of contract

The “required classification” of a contract typically refers to the specific categorization of a contract based on legal or contextual needs. However, to clarify, there are certain classifications of contracts that are “required” or essential for understanding their validity, enforceability, and implications in law. These include:

1. Required Classification Based on Validity

For a contract to be legally binding and enforceable, it must fall into one of the following categories:

- Valid Contract: A legally binding contract where all essential elements are met (offer, acceptance, consideration, capacity, and legality).

- Void Contract: A contract with no legal effect because it lacks one or more necessary elements (e.g., illegal purpose).

- Voidable Contract: A contract that is valid but can be voided by one party due to factors like fraud, duress, or misrepresentation.

- Illegal Contract: A contract for an unlawful purpose, which is not enforceable by law.

2. Required Classification Based on Enforceability

- Express Contracts: Terms explicitly stated by the parties, either in writing or orally. This is the most common form of required contract classification when the terms need clear communication.

- Implied Contracts: Created by the actions or conduct of the parties, even if not formally written or spoken.

- Quasi-Contracts: Imposed by the court to prevent unjust enrichment when no contract exists, often in situations where one party benefits at the expense of another.

3. Required Classification Based on Performance

- Executed Contracts: Contracts where all terms have been fully performed by both parties.

- Executory Contracts: Contracts where performance is still pending by one or both parties.

These classifications are typically required for determining whether a contract is enforceable, valid, or can be legally acted upon in specific situations. Each classification helps clarify the rights and obligations of the parties involved.

Who is Required Classification of contract

The required classification of a contract typically pertains to the parties involved in the contract as well as legal professionals, including lawyers, judges, and courts. Here’s how each group might need or use these classifications:

1. Parties Involved in the Contract

- Business Owners, Employers, Individuals: Any individual or business entering into a contract will need to understand how the contract is classified in order to know their obligations, rights, and the consequences of non-performance or breach.

- Contract Negotiators: They need to classify the contract properly to ensure that all necessary legal components are included and that both parties’ interests are adequately protected.

2. Legal Professionals

- Lawyers and Attorneys: They help their clients understand and navigate contracts. They need to classify the contract accurately to assess enforceability, risk, and the best course of action in case of disputes.

- Judges and Courts: When a dispute arises, judges or arbitrators classify contracts to determine whether the terms were met, whether the contract is valid, void, voidable, or illegal, and the applicable remedies.

3. Legal Systems and Regulatory Authorities

- Government Agencies: In some cases, regulations or laws require specific classifications of contracts for taxation, licensing, or other regulatory purposes (such as employment contracts or real estate agreements).

- Arbitration Panels: In non-court resolutions, arbitration bodies need to classify contracts to apply the correct rules for dispute resolution.

In summary, classification of a contract is required for any party entering into the contract (to understand their obligations and enforceability), but it is especially crucial for legal professionals and courts when interpreting, enforcing, or resolving disputes related to the contract.

When is Required Classification of contract

The required classification of a contract becomes necessary at various stages throughout the lifecycle of the contract. Here are the key moments when the classification is required:

1. At the Formation Stage

- When creating the contract, the classification is important to ensure that all the essential elements of the contract (offer, acceptance, consideration, and legality) are present. For example, distinguishing between a bilateral or unilateral contract helps in determining the type of agreement being formed.

2. When Executing the Contract

- During performance, classifying the contract as executed (fully performed) or executory (yet to be performed) helps both parties understand their current obligations. If any issues arise during the performance, understanding the classification helps to resolve them, especially in terms of breach or performance expectations.

3. When Determining Enforceability

- At the point of a legal dispute or breach (e.g., when one party fails to fulfill their obligations or a dispute arises), classification is crucial to determine if the contract is valid, voidable, void, or illegal. For instance, if a void contract is disputed, the court will assess its validity.

4. When Considering Remedies for Breach

- If a party breaches the contract, the classification helps determine the appropriate legal remedies. For instance, whether damages or specific performance will be applicable based on whether the contract is valid or voidable, and whether the breach is material.

5. During Legal Disputes or Litigation

- In court proceedings or alternative dispute resolution (ADR), legal professionals will classify the contract to understand its enforceability, the rights and duties of the parties, and the nature of the dispute. Whether a contract is express or implied can influence how the case is argued and what evidence is required.

6. For Regulatory and Compliance Purposes

- Certain contracts may be subject to regulations that require classification to ensure compliance. For example, employment contracts or real estate contracts may need classification under specific legal guidelines or regulatory frameworks.

7. When Modifying the Contract

- If any changes or amendments are made to the contract, the classification helps in understanding whether those modifications are enforceable and how they impact the existing terms. For instance, if the contract was executory, modifying performance expectations may affect the classification.

In summary, the required classification of a contract is important before execution (to ensure legality and enforceability), during execution (to track performance), and after disputes or legal challenges arise (to determine remedies, validity, and rights).

Where is Required Classification of contract

The required classification of a contract is relevant in several settings or locations where contracts are formed, executed, interpreted, or disputed. Here are the key places where classification is required:

1. In Contract Formation (Between Parties)

- Business negotiations or discussions: When two or more parties are discussing terms and agreeing to a contract, classification helps to determine the type of agreement being made (e.g., bilateral, unilateral, express, or implied). This classification ensures that both parties understand their rights and obligations.

- Written contracts: The classification is explicitly stated or implied in the contract document itself (such as identifying it as a contract of sale, service, employment, etc.).

2. In Legal and Judicial Settings

- Courts: When a legal dispute arises regarding a contract, the classification is required to determine whether the contract is valid, void, voidable, or illegal. Courts often classify contracts during litigation or arbitration to decide the enforceability of terms.

- Arbitration and Mediation: In cases where the dispute is resolved through alternative dispute resolution (ADR), classifications help the arbitrator or mediator understand the nature of the contract, the roles of the parties involved, and the potential legal remedies.

3. In Regulatory and Compliance Frameworks

- Government Agencies: Regulatory bodies or agencies may require classification when monitoring or reviewing contracts in specific industries (e.g., labor contracts, real estate contracts, or government procurement contracts). This ensures compliance with legal, tax, or industry-specific regulations.

- Tax Authorities: Classifying contracts is necessary to determine tax obligations, such as whether a contract is classified as a sale of goods, a lease, or an employment agreement, each of which has different tax implications.

4. In Business and Commercial Transactions

- Business Agreements: Companies or individuals entering into contracts (e.g., sale of goods, service agreements, leases) will classify contracts to understand the terms and legal requirements. This is especially important for ensuring clarity on obligations and potential risks.

- Contract Management Systems: In large organizations, contract management software often requires classification for categorizing contracts based on type (employment, sales, etc.) and tracking their performance and obligations.

5. In Contract Review and Enforcement

- Legal Advisors: Lawyers classify contracts to review whether the terms are enforceable, identify the rights of the parties, and assess the risk of litigation or breach. This classification helps determine how the contract should be executed or whether any modifications are required.

- Contract Audits: Organizations may perform audits on contracts to ensure they align with regulatory standards and internal policies, and classification plays a crucial role in the auditing process.

6. In International or Cross-Border Transactions

- Cross-border Agreements: In international contracts, classification helps determine which country’s laws apply and which legal frameworks govern the agreement. Contracts might be classified as trade agreements, joint ventures, or international sales contracts, with specific legal implications in each jurisdiction.

7. In Financial or Insurance Transactions

- Loans and Mortgages: In the context of loans, mortgages, or insurance contracts, classification helps in understanding the terms of repayment, interest, and default, and assists in assessing whether the contract is executory or executed.

In summary, the required classification of a contract is essential wherever contracts are made, interpreted, or enforced, including business transactions, legal proceedings, regulatory settings, and financial or commercial environments. It ensures clarity, legal enforceability, and proper application of rights and duties across all parties involved.

How is Required Classification of contract

The required classification of a contract is determined through a legal analysis of the contract’s terms, parties’ intentions, and the nature of the agreement. Here’s how contracts are typically classified:

1. By the Type of Agreement

- Bilateral Contracts: These are contracts where both parties make promises. For example, in a sales contract, one party promises to deliver goods, and the other promises to pay for them.

- Unilateral Contracts: These involve only one party making a promise in exchange for an act. For instance, a reward contract (e.g., “I will pay $100 to anyone who finds my lost dog”) is unilateral because the reward is given only when the act (finding the dog) is performed.

2. By Performance

- Executed Contracts: These are contracts where both parties have fully performed their obligations. For example, a contract for the sale of goods where the goods are delivered and payment has been made.

- Executory Contracts: These are contracts where one or both parties have not yet fully performed their obligations. For instance, a contract for future delivery of goods is executory until the goods are delivered.

3. By Validity

- Valid Contracts: Contracts that meet all legal requirements (offer, acceptance, consideration, and capacity) and are enforceable by law.

- Void Contracts: These have no legal effect, either because they lack a legal purpose or essential elements, such as in the case of a contract for illegal activities.

- Voidable Contracts: These are contracts that are initially valid but can be voided by one party due to factors like fraud, coercion, or lack of capacity (e.g., a contract signed under duress).

- Illegal Contracts: Contracts made for illegal purposes, which cannot be enforced by law.

4. By the Nature of the Consideration

- Contract of Sale: Involves the transfer of ownership of goods in exchange for money.

- Contract for Services: Involves the provision of services in exchange for payment.

5. By Express or Implied Terms

- Express Contracts: These are contracts where the terms are explicitly stated by the parties, either orally or in writing. For example, an employment contract where the job role, salary, and other terms are clearly stated.

- Implied Contracts: These arise from the conduct of the parties or the circumstances, even if not explicitly stated. For instance, if you order food at a restaurant, an implied contract exists for the provision of the meal at the agreed price.

6. By the Law Governing the Contract

- Civil Contracts: Governed by civil law (e.g., contracts related to personal transactions, property).

- Commercial Contracts: Governed by commercial law (e.g., contracts between businesses for goods or services).

- Contract under Statute: Some contracts are governed by specific statutes or regulations (e.g., consumer protection laws, labor laws, etc.).

7. By the Intention of the Parties

- Formal Contracts: These require a specific form or procedure to be legally binding, such as a written agreement or notarized document (e.g., real estate contracts, wills).

- Informal Contracts: These do not require a specific format and are usually verbal or written in a less formal manner but still legally enforceable under certain conditions.

8. By Risk and Responsibility

- Contracts of Adhesion: These are agreements where one party has significantly more power than the other in setting terms, often seen in insurance contracts, standard form agreements, etc.

- Conditional Contracts: These depend on the occurrence of a specific event or condition before they can be enforced (e.g., an insurance contract that depends on an accident happening).

How Classification is Determined

Classification is determined based on:

- Intent of the Parties: What the parties intended when they entered the agreement. For example, if both parties agreed to exchange promises, it’s likely a bilateral contract.

- Performance: Whether the contract has been executed or is still executory.

- Legal Requirements: Whether the contract complies with statutory requirements, such as the Statute of Frauds, which might require certain contracts (like real estate agreements) to be in writing.

- Circumstances and Conduct: Whether the contract is implied by the conduct of the parties (e.g., continuing to provide services and accept payment can imply an agreement).

Summary

The classification of a contract involves analyzing its nature, the promises made, the performance status, and legal compliance. This classification helps in understanding the contract’s enforceability, the parties’ obligations, and the remedies available in case of a dispute. It’s essential for both practical execution (such as managing risk or performing obligations) and legal interpretation (such as resolving disputes).

Case Study on Classification of contract

Background:

A company named TechSolutions Ltd. (the buyer) enters into a contract with Global Electronics Corp. (the seller) to purchase 100 units of a new type of computer component for $500,000. The agreement stipulates that the units will be delivered within six months. Both parties have signed the contract, and the buyer agrees to pay upon delivery.

However, three months into the contract, TechSolutions Ltd. faces financial difficulty and refuses to continue with the purchase. The seller, Global Electronics Corp., seeks legal action for breach of contract and seeks to classify the contract in a manner that allows them to recover the payment.

Classification of the Contract:

1. By Formation:

- Bilateral Contract: This is a bilateral contract because both parties (TechSolutions and Global Electronics) made mutual promises: TechSolutions promised to pay for the goods, and Global Electronics promised to deliver the components. Since both parties have obligations, this falls under a bilateral contract.

2. By Performance:

- Executory Contract: The contract is still executory at the time of the dispute, as neither party has fully performed its obligations. The buyer hasn’t paid the $500,000, and the seller hasn’t delivered the components yet. The contract is intended to be executed within six months, so the contract remains executory until performance happens.

3. By Validity:

- Valid Contract: This is a valid contract since it meets all the requirements for enforceability:

- Offer and Acceptance: Global Electronics made an offer, and TechSolutions accepted.

- Consideration: TechSolutions agreed to pay $500,000, and Global Electronics agreed to deliver the goods.

- Legality: The contract is for a legal purpose (the sale of computer components).

- Capacity: Both parties had the legal capacity to contract.

4. By Enforceability:

- Breach and Remedy: Since the buyer refuses to perform its obligations, the seller is now entitled to claim damages or potentially specific performance (forcing TechSolutions to fulfill the contract). This would depend on the jurisdiction’s laws regarding breach of contract and the seller’s preferred remedy.

5. By Nature of the Consideration:

- Contract of Sale: This contract qualifies as a contract of sale because it involves the exchange of goods (computer components) for money ($500,000).

6. By the Law Governing the Contract:

- Commercial Contract: Since both parties are businesses, this is a commercial contract, governed by commercial law, likely including the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) if it is in the United States or similar commercial laws in other jurisdictions.

Legal Dispute:

TechSolutions Ltd. fails to pay and attempts to cancel the contract. Global Electronics Corp. sues for breach of contract, arguing that the contract was executory and valid, and that TechSolutions’ refusal to perform constitutes a breach.

Legal Analysis:

- Classification of the Contract as an executory contract means that the buyer is required to pay upon delivery. Since delivery hasn’t occurred yet, the contract is still in force, and the seller can claim damages for non-performance.

- Breach of Contract: TechSolutions’ refusal to perform its obligation (payment) breaches the agreement, which entitles Global Electronics to claim compensatory damages or specific performance.

- Specific Performance: In this case, if damages are insufficient, Global Electronics might ask the court to order specific performance—forcing TechSolutions to pay the agreed amount, particularly if the components are unique or difficult to replace.

Outcome:

- The court classifies the contract as executory and bilateral.

- Since the contract is valid and the buyer is in breach, the court orders TechSolutions Ltd. to pay the agreed $500,000 or face further legal action.

- Global Electronics may be awarded damages for any financial loss caused by the breach or specific performance depending on the goods’ uniqueness and the jurisdiction’s laws.

Conclusion:

This case demonstrates how the classification of a contract plays a critical role in determining the rights and obligations of the parties involved. The executory nature of the contract and the bilateral exchange of promises became central to the legal analysis and the remedy (damages or specific performance). The classification also helped establish the legal basis for enforcing the contract and resolving the breach.

White paper on Classification of contract

Introduction

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties. Understanding how contracts are classified is crucial for both parties involved, as it determines the rights, obligations, and remedies available in the event of a dispute. This white paper explores the different classifications of contracts, their legal significance, and the factors that influence these classifications.

1. Classification Based on Formation

Contracts can be classified according to how they are formed, and the nature of the promises exchanged.

- Bilateral Contracts A bilateral contract is formed when both parties exchange mutual promises to perform certain actions. The most common type of contract, bilateral contracts are seen in most everyday transactions. For example, in a purchase agreement, one party promises to deliver goods, and the other promises to pay for them.

- Key Features:

- Two or more promises are made.

- Both parties are legally obligated to fulfill their promises.

- Example: Sale of goods, employment contracts.

- Key Features:

- Unilateral Contracts A unilateral contract involves a promise made by one party in exchange for an act. The contract is only completed when the act specified by the promisor is carried out. An example of a unilateral contract is a reward offer: “I will pay $100 to anyone who finds my lost dog.”

- Key Features:

- Only one party makes a promise.

- The contract is executed only upon completion of the specified act.

- Example: Reward contracts, contests.

- Key Features:

2. Classification Based on Performance

Contracts can also be classified according to whether they have been fully performed or if performance is still pending.

- Executed Contracts An executed contract is one where both parties have fulfilled their obligations. For example, a contract for the sale of goods is executed once the goods are delivered, and the buyer has paid.

- Key Features:

- Both parties have performed their obligations.

- The contract is considered completed.

- Example: A completed sale transaction.

- Key Features:

- Executory Contracts An executory contract refers to a contract in which some or all obligations remain unfulfilled. For instance, a contract for the delivery of goods in the future is executory until the delivery occurs.

- Key Features:

- Some or all obligations are yet to be performed.

- The contract is ongoing.

- Example: A contract to build a house.

- Key Features:

3. Classification Based on Validity

Another key classification of contracts is based on their legal validity. A contract may be valid, void, voidable, or illegal.

- Valid Contracts A valid contract is one that meets all the legal requirements for enforceability, including offer, acceptance, consideration, capacity, and legality. For example, an agreement to sell goods where both parties intend to be bound and all terms are legal.

- Key Features:

- The contract is legally enforceable.

- Meets all essential elements.

- Example: A standard sales contract.

- Key Features:

- Void Contracts A void contract is an agreement that lacks one or more essential elements, making it unenforceable from the outset. For example, a contract for the sale of illegal drugs is void.

- Key Features:

- The contract has no legal effect.

- Cannot be enforced by law.

- Example: A contract for illegal activities.

- Key Features:

- Voidable Contracts A voidable contract is valid but can be voided by one party under certain circumstances, such as fraud, misrepresentation, or coercion. A contract entered into by a minor may be voidable at the minor’s discretion.

- Key Features:

- Initially valid but subject to cancellation.

- One party has the right to void the contract.

- Example: Contracts made under duress or fraud.

- Key Features:

- Illegal Contracts An illegal contract involves an agreement to engage in unlawful activities, which makes the contract unenforceable and void from the beginning.

- Key Features:

- Involves unlawful subject matter.

- Cannot be enforced by law.

- Example: A contract for the sale of counterfeit goods.

- Key Features:

4. Classification Based on Enforceability

Contracts can also be classified by how they are enforced. This category includes express, implied, and quasi contracts.

- Express Contracts An express contract is formed when the terms of the agreement are explicitly stated, either orally or in writing. For instance, a written lease agreement is an express contract where the terms (rent, duration, etc.) are clearly defined.

- Key Features:

- Terms are explicitly stated by the parties.

- Can be oral or written.

- Example: A written employment contract.

- Key Features:

- Implied Contracts An implied contract arises from the conduct of the parties, rather than their explicit words. For instance, when you order food at a restaurant, there is an implied contract to pay for the meal once it is served.

- Key Features:

- Terms are not stated but inferred from conduct.

- Arises from the actions or circumstances of the parties.

- Example: A contract for services where payment is implied by the provision of services.

- Key Features:

- Quasi Contracts A quasi contract is not a real contract but is imposed by the courts to prevent unjust enrichment. For example, if one party mistakenly pays for goods they never received, the court may create a quasi contract requiring reimbursement.

- Key Features:

- Not an actual contract.

- Imposed by the courts to prevent unjust enrichment.

- Example: Reimbursement for mistaken payment.

- Key Features:

5. Classification Based on the Nature of Consideration

Consideration refers to what each party offers in a contract, and contracts can be classified based on the nature of that consideration.

- Contracts of Sale These are agreements in which one party transfers ownership of goods or property in exchange for money or other value. For example, the sale of a car where the buyer pays the seller.

- Key Features:

- Exchange of goods or property for money.

- Common in commercial transactions.

- Example: A sale agreement for electronics.

- Key Features:

- Contracts for Services In a contract for services, one party agrees to provide services, and the other agrees to pay for them. For example, a contract for hiring a contractor to build a home.

- Key Features:

- Involves the provision of services rather than goods.

- Often includes performance-based terms.

- Example: A service agreement with a lawyer or accountant.

- Key Features:

Conclusion

The classification of contracts is essential for understanding the rights and obligations of parties involved in an agreement. It determines the enforceability, scope, and remedies available for breach. By categorizing contracts based on formation, performance, validity, enforceability, and consideration, parties can better navigate their contractual obligations and ensure that they are entering into agreements that are legally sound.

Understanding these classifications is key to effective contract management, dispute resolution, and risk mitigation, ensuring that the intentions of all parties are respected and upheld in the event of a breach or disagreement.

Industrial Application of Classification of contract

Courtesy: Learning with Dr. Shivangi

The classification of contracts plays a critical role in various industrial sectors. Understanding the different types of contracts and how they are categorized is crucial for businesses to manage risks, ensure compliance, and optimize operations. This section explores the industrial applications of contract classification, illustrating how it impacts key sectors such as manufacturing, construction, technology, and services.

1. Manufacturing Industry

In the manufacturing sector, contracts are frequently used for supply agreements, joint ventures, and procurement of raw materials. The classification of contracts is vital to ensure that all parties understand their obligations and to manage risks effectively.

- Supply Contracts (Sales Contracts):

- Classification: Contract of Sale (Bilateral, Executory)

- Application: Manufacturers enter into contracts with suppliers for the procurement of raw materials, where the supplier promises to deliver materials, and the manufacturer promises to pay. Understanding the classification ensures that payment terms, delivery schedules, and quality standards are clearly defined, reducing the risk of disputes.

- Outsourcing and Subcontracting:

- Classification: Contract for Services (Bilateral, Executory)

- Application: Manufacturing companies often outsource specific tasks such as assembly or packaging. These are typically classified as contracts for services, where the subcontractor agrees to perform a task for a fee. Accurate classification helps in ensuring that performance expectations, timelines, and liabilities are clearly stated, minimizing the risk of delays and breaches.

- Long-Term Supply Agreements:

- Classification: Executory Contract (Bilateral, Executory)

- Application: For long-term supply arrangements, the contract is executed over a period, and the classification as executory helps to determine the milestones and penalties for non-performance, which is crucial for financial forecasting and inventory management.

2. Construction Industry

The construction industry is highly reliant on contracts for large-scale projects, including building infrastructure, residential complexes, and commercial properties. Proper classification of contracts ensures clarity of roles, responsibilities, and timelines.

- Construction Contracts:

- Classification: Bilateral Contract, Executory Contract

- Application: In construction, both the contractor and the client make mutual promises. The contractor promises to deliver a completed project, and the client agrees to pay for it. The classification of these contracts helps determine payment schedules (e.g., progress payments), deadlines, and specifications for performance.

- Subcontracting and Project Financing:

- Classification: Contract for Services (Bilateral, Executory)

- Application: A construction firm might hire subcontractors to complete parts of a project. Subcontracting agreements are typically classified as contracts for services. Classifying these correctly ensures the contractor and subcontractor’s duties are clear, ensuring effective project management.

- Fixed-Price and Time-and-Materials Contracts:

- Classification: Executory Contract (Bilateral)

- Application: Construction contracts are often classified as fixed-price or time-and-materials contracts, which dictate how costs will be handled. This classification helps manage project scope, budgeting, and changes during construction. The type of contract affects how payments are made and the legal implications for changes in scope.

3. Technology and Software Industry

In the technology sector, contracts are vital for software development, licensing agreements, cloud services, and collaboration between companies. Contract classification helps define terms of use, delivery timelines, and intellectual property rights.

- Software Development Agreements:

- Classification: Bilateral Contract (Executory)

- Application: In software development, a contract is formed when a developer agrees to build and deliver a product in exchange for compensation. Classifying this as a bilateral, executory contract helps set clear expectations about timelines, milestones, intellectual property ownership, and delivery.

- Licensing Contracts:

- Classification: Contract for Services (Bilateral)

- Application: Software licensing agreements often involve a service-based contract, where the software developer provides ongoing support, updates, and maintenance in exchange for recurring payments. Proper classification ensures clarity on service obligations and payment structures, preventing potential legal issues.

- Outsourcing and Cloud Services:

- Classification: Contract for Services (Executory)

- Application: Technology firms that outsource specific IT functions, like data storage or cloud computing services, enter into service contracts. These contracts may be executory, as services are ongoing, and it’s essential to define service levels, downtime penalties, and data security measures.

4. Energy and Utilities Industry

The energy and utilities sectors rely on large-scale agreements for supply, distribution, and infrastructure development. Contract classification ensures proper allocation of risks, costs, and responsibilities.

- Energy Supply Agreements:

- Classification: Contract of Sale (Bilateral, Executory)

- Application: Utility companies enter into contracts with energy suppliers for the procurement of energy (such as electricity or gas). The classification of these contracts as contracts of sale ensures clarity around delivery schedules, payment terms, and compliance with regulations.

- Joint Ventures in Energy Projects:

- Classification: Joint Venture Contracts (Bilateral)

- Application: In large-scale energy projects, such as oil extraction or renewable energy facilities, companies often enter joint ventures. These contracts require clear classification to determine each party’s contribution, liabilities, and profit-sharing arrangements.

- Power Purchase Agreements (PPA):

- Classification: Executory Contract

- Application: In a PPA, one party agrees to purchase electricity at a set price for a certain period. These contracts are typically executory, as payments are made over time and depend on future electricity delivery. Classifying these contracts accurately helps manage long-term obligations and regulatory compliance.

5. Service Industry (Consulting, Legal, Healthcare)

In the service industry, contracts are essential for defining the relationship between service providers and clients. Accurate classification of contracts allows service providers to clarify their responsibilities and limits of liability.

- Consulting Agreements:

- Classification: Contract for Services (Bilateral)

- Application: In consulting, the service provider agrees to deliver expertise in exchange for payment. The classification of these contracts ensures that performance expectations are clearly defined, such as timelines, deliverables, and fees.

- Employment Contracts:

- Classification: Bilateral Contract (Executory)

- Application: In the service sector, employment contracts specify the duties of employees and the compensation offered by employers. These are bilateral contracts that involve mutual promises and are classified based on the terms of employment, such as salary, working hours, and benefits.

- Healthcare Service Contracts:

- Classification: Contract for Services (Bilateral)

- Application: In healthcare, providers enter into contracts with patients to deliver medical services in exchange for payment. The classification helps define the terms of care, payment schedules, and liability for any negligence or malpractice.

Conclusion

The classification of contracts is a fundamental aspect of industrial operations across various sectors. Whether in manufacturing, construction, technology, energy, or services, proper contract classification helps ensure clarity, minimize risks, and protect the interests of all parties involved. It defines the nature of the agreement, sets out performance expectations, and facilitates dispute resolution.

By classifying contracts accurately, industries can streamline their contractual relationships, enhance operational efficiency, and ensure that they remain compliant with relevant regulations and standards.

References

- “Contracts is Not Promise; Contract is Consent”. Suffolk U. L. Rev. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ “Case Note – Contract Law – Rule of Law Institute of Australia”, Rule of Law Institute of Australia, 2018-05-31, retrieved 2018-09-14

- ^ “International Legal Research”. law.duke.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ Hans Wehberg, Pacta Sunt Servanda, The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Oct., 1959), p.775.; Trans-Lex.org Principle of Sanctity of contracts

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts

- ^ Beatson, Anson’s Law of Contract (1998) 27th ed. OUP, p.21

- ^ Martin, E [ed] & Law, J [ed], Oxford Dictionary of Law, ed6 (2006, London:OUP).

- ^ Reuer, Jeffrey J.; Ariño, Africa (March 2007). “Strategic alliance contracts: dimensions and determinants of contractual complexity”. Strategic Management Journal. 28 (3): 313–330. doi:10.1002/smj.581.

- ^ For the assignment of claim see Trans-Lex.org

- ^ Malhotra, Deepak; Murnighan, J. Keith (2002). “The Effects of Contracts on Interpersonal Trust”. Administrative Science Quarterly. 47 (3): 534–559. doi:10.2307/3094850. ISSN 0001-8392. JSTOR 3094850. S2CID 145703853.

- ^ Poppo, Laura; Zenger, Todd (2002). “Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements?”. Strategic Management Journal. 23 (8): 707–725. doi:10.1002/smj.249. ISSN 1097-0266.

- ^ The Hawala Alternative Remittance System and its Role in Money Laundering (PDF) (Report).

- ^ Badr, Gamal Moursi (Spring 1978). “Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems”. American Journal of Comparative Law. 26 (2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24–25, 1977]): 187–98. doi:10.2307/839667. JSTOR 839667.

- ^ Badr, Gamal Moursi (Spring 1978). “Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems”. The American Journal of Comparative Law. 26 (2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24–25, 1977]): 187–98 [196–8]. doi:10.2307/839667. JSTOR 839667.

- ^ Egyptian Civil Code 1949, Article 1

- ^ Willmott, L, Christensen, S, Butler, D, & Dixon, B 2009 Contract Law, Third Edition, Oxford University Press, North Melbourne

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bernstein DE. (2008). Freedom of Contract. George Mason Law & Economics Research Paper No. 08-51.

- ^ Douglas D. (2002). Contract Rights and Civil Rights. Michigan Law Review.

- ^ Consumer Protection (Fair Trading) Act 2003 (Singapore)

- ^ … indeed the Code was neither published nor adopted by the UK, instead being privately published by an Italian University

- ^ Atiyah PS. (1986) Medical Malpractice and Contract/Tort Boundary. Law and Contemporary Problems.

- ^ In England, contracts of employment must either be in writing (Employment Rights Act 1996), or else a memorandum of the terms must be promptly supplied; and contracts for the sale of land, and most leases, must be completed by deed (Law of Property Act 1925).

- ^ “Contracts”. www.lawhandbook.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hadley v Baxendale [1854] EWHC J70, ER 145, High Court (England and Wales).

- ^ as in Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd and The Mihalis Angelos

- ^ The Indian Contract Act 1872 s.2a

- ^ Enright, Máiréad (2007). Principles of Irish Contract Law. Clarus Press.

- ^ The Indian Contract Act 1872 s.2b

- ^ DiMatteo L. (1997). The Counterpoise of Contracts: The Reasonable Person Standard and the Subjectivity of Judgment Archived 2013-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. South Carolina Law Review.

- ^ George Hudson Holdings Ltd v Rudder (1973) 128 CLR 387 [1973] HCA 10, High Court (Australia).

- ^ The Uniform Commercial Code disposes of the mirror image rule in §2-207, although the UCC only governs transactions in goods in the USA.

- ^ George, James (February 2004). “Contract law—it’s only as good as the people”. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 22 (1): 217–224. doi:10.1016/S0733-8627(03)00094-4. PMID 15062506.

- ^ Feinman JM, Brill SR. (2006). Is an Advertisement an Offer? Why it is, and Why it Matters[permanent dead link]. Hastings Law Journal.

- ^ Wilmot et al, 2009, Contract Law, Third Edition, Oxford University Press, page 34

- ^ Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 1 WLR 1204

- ^ Harris v Nickerson (1873) LR8QB 286[permanent dead link]

- ^ Household Fire Insurance v Grant 1879

- ^ Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co [1892] EWCA Civ 1, [1893] 2 QB 256, Court of Appeal (England and Wales).

- ^ Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v. Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd Archived 2016-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, 1953, 1 Q.B. 401

- ^ Currie v Misa (1875) LR 10 Ex 893

- ^ Enright, Máiréad (2007). Principles of Irish Contract Law. Dublin 8: Clarus Press. p. 75.

- ^ Wade v Simeon (1846) 2 CB 548

- ^ White v Bluett (1853) 2 WR 75

- ^ Bronaugh R. (1976). Agreement, Mistake, and Objectivity in the Bargain Theory of Conflict. William & Mary Law Review.

- ^ UCC § 2-205

- ^ Collins v. Godefroy (1831) 1 B. & Ad. 950.

- ^ The Indian Contract Act 1872 s.2d

- ^ Chappell & Co Ltd v. Nestle Co Ltd [1959] 2 All ER 701 in which the wrappers from three chocolate bars was held to be part of the consideration for the sale and purchase of a musical recording.

- ^ e.g. P.S. Atiyah, “Consideration: A Restatement” in Essays on Contract (1986) p.195, Oxford University Press

- ^ Jump up to:a b L’Estrange v Graucob [1934] 2 KB 394.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52, (2004) 219 CLR 165 (11 November 2004), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co [1951] 1 KB 805

- ^ Balmain New Ferry Co Ltd v Robertson [1906] HCA 83, (1906) 4 CLR 379 (18 December 1906), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Baltic Shipping Company v Dillon [1993] HCA 4, (1993) 176 CLR 344, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Michida S. (1992) Contract Societies: Japan and the United States Contrasted. Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal.

- ^ “Laws affecting contracts”. business.gov.au. 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ^ Taylor, Martyn (2021-09-01). “Sale and Storage of Goods in Australia: Overview”. Practical Law. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ^ Trans-Lex.org: international principle

- ^ Burchfield, R.W. (1998). The New Fowler’s Modern English Usage (Revised 3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 820–821. ISBN 0198602634.

Expressed or conveyed by speech instead of writing; oral… e.g. verbal agreement, contract, evidence

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (1999). Black’s Law Dictionary: Definitions of the Terms and Phrases of American and English Jurisprudence, Ancient and Modern. West Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-314-15234-3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Shire of Hastings [1977] UKPC 13, (1977) 180 CLR 266, Privy Council (on appeal from Australia).

- ^ Fry v. Barnes (1953) 2 D.L.R. 817 (B.C.S.C)

- ^ Hillas and Co. Ltd. v. Arcos Ltd. (1932) 147 LT 503

- ^ See Aiton Australia Pty Ltd v Transfield Pty Ltd (1999) 153 FLR 236 Thomson Reuters Archived 2016-08-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whitlock v Brew [1968] HCA 71, (1968) 118 CLR 445 (31 October 1968), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Three Rivers Trading Co., Ltd. v. Gwinear & District Farmers, Ltd. (1967) 111 Sol. J. 831

- ^ “Cutter v Powell” (1795) 101 ER 573

- ^ Swarbrick, D., Modern Engineering (Bristol) Ltd v Gilbert Ash (Northern) Ltd: HL 1974, updated on 4 August 2022, accessed on 17 September 2024. This case is referred to as an authority in this regard in the High Court case of Stocznia Gdynia SA v Gearbulk Holdings Ltd., paragraph 9, delivered on 2 May 2008, accessed on 17 September 2024

- ^ Moloo, Rahim; Jacinto, Justin (2010). Mediation Techniques: Drafting International Mediation Clauses. London: International Bar Association. ISBN 9780948711237.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gillies P. (1988). Concise Contract Law, p. 105. Federation Press.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Luna Park (NSW) Ltd v Tramways Advertising Pty Ltd [1938] HCA 66, (1938) 61 CLR 286 (23 December 1938), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d West GD, Lewis WB., Contracting to Avoid Extra-Contractual Liability—Can Your Contractual Deal Ever Really Be the “Entire” Deal? The Business Lawyer, volume 64, August 2009, archived on 7 January 2011, accessed on 17 September 2024.

- ^ Koffman L, MacDonald E. (2007). The Law of Contract. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Burling JM. (2011). Research Handbook on International Insurance Law and Regulation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ^ Poussard v Spiers and Pond (1876) 1 QBD 410

- ^ Bettini v Gye (1876) 1 QBD 183

- ^ As added by the Sale of Goods Act 1994 s4(1).

- ^ Primack MA. (2009). Representations, Warranties and Covenants: Back to the Basics in Contracts. National Law Review.

- ^ Ferara LN, Philips J, Runnicles J. (2007). Some Differences in Law and Practice Between U.K. and U.S. Stock Purchase Agreements Archived 2013-05-14 at the Wayback Machine. Jones Day Publications.

- ^ Bannerman v White [1861] EngR 713; (1861) 10 CBNS 844, Court of Common Pleas (United Kingdom).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bissett v Wilkinson [1927] AC 177.

- ^ Tettenborn et al (2017), Contractual Duties: Performance, Breach, Termination and Remedies, second edition, at paragraph 10-036, quoted by Klein J. in England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division), C21 London Estates Ltd v Maurice Macneill Iona Ltd & Anor, [2017] EWHC 998 (Ch), delivered 10 May 2017, accessed 8 September 2023

- ^ See for a discussion of the position in English law, the article on Capacity in English law

- ^ Philippine Civil Code (Republic Act No. 386) Archived 2022-05-11 at the Wayback Machine Article 39

- ^ Elements of a Contract – Contracts

- ^ Edge, Robert G. (1 December 1967). “Voidability of Minors’ Contracts: A Feudal Doctrine in a Modern Economy Economy”. Georgia Law Review. 1 (2): 40.

- ^ Chandler, Adrian; Brown, Ian (2007). Q and A: Law of Contract. U.K.: Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780199299553.

- ^ Civil Law Act 1909 s35-36 (Singapore).

- ^ Minors’ Contracts Act 1987

- ^ Mental Capacity Act 2008 s4 (Singapore)

- ^ Mental Capacity Act 2008 s11 (Singapore)

- ^ Part 5 of the Mental Capacity Act 2008 (Singapore)

- ^ The Moorcock (1889) 14 PD 64.

- ^ J Spurling Ltd v Bradshaw [1956] EWCA Civ 3, [1956] 2 All ER 121, Court of Appeal (England and Wales)

- ^ Hutton v Warren [1836] M&W 466

- ^ Marine Insurance Act 1909 s.17 (Singapore)

- ^ Marine Insurance Act 1909 s.5 (Singapore)

- ^ Insurance Act 1966 s.146 (Singapore)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Report on Reforming Insurance Law in Singapore (Singapore Academy of Law)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Con-stan Industries of Australia Pty Ltd v Norwich Winterthur Insurance (Australia) Ltd [1986] HCA 14, (1986) 160 CLR 226 (11 April 1986), High Court (Australia).

- ^ McKendrick, E. (2000), “Contract Law”, Fourth edition, p. 377

- ^ Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977

- ^ Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [1962] 1 All ER 474; see also Associated Newspapers Ltd v Bancks [1951] HCA 24, (1951) 83 CLR 322, High Court (Australia).

- ^ The Mihailis Angelos [1971] 1 QB 164

- ^ Bellgrove v Eldridge [1954] HCA 36, (1954) 90 CLR 613 (20 August 1954), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Jump up to:a b McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission [1951] HCA 79, (1951) 84 CLR 377, High Court (Australia).

- ^ [1972] 1 QB 60

- ^ Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd [1914] UKHL 1, [1915] AC 79 at 86 per Lord Dunedin, House of Lords (UK).

- ^ Awad v. Dover, 2021 ONSC 5437 (CanLII)

- ^ Fern Investments Ltd. v. Golden Nugget Restaurant (1987) Ltd., 1994 ABCA 153 (CanLII)

- ^ Bidell Equipment LP v Caliber Midstream GP LLC, 2020 ABCA 478 (CanLII)

- ^ Philippine Civil Code (Republic Act No. 386) Archived 2022-05-11 at the Wayback Machine Articles 2226–2228

- ^ Cavendish Square Holdings BV v Makdessi [2015] UKSC 67 (Cavendish)

- ^ Paciocco v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2016] HCA 28

- ^ The UCC states, “Consequential damages… include any loss… which could not reasonably be prevented by cover or otherwise.” UCC 2-715.In English law the chief authority on mitigation is British Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co v Underground Electric Railway Co of London[1912] AC 673, see especially 689 per Lord Haldane.

- ^ M. P. Furmston, Cheshire, Fifoot & Furmston’s Law of Contract, 15th edn (OUP: Oxford, 2007) p.779.

- ^ M.P. Furmston, Cheshire, Fifoot & Furmston’s Law of Contract, 15th edn (OUP: Oxford, 2007) p.779 n.130.

- ^ Sotiros Shipping Inc v Sameiet, The Solholt [1983] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 605.

- ^ See also Alexander v Cambridge Credit Corp Ltd (1987) 9 NSWLR 310.

- ^ “13th Amendment to the United States Constitution”. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ Public Contracts (Amendments) Regulations 2009, (SI 2009–2992)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, Book Three, Chapter Seven, Article 563

- ^ Jump up to:a b Knapp, Charles; Crystal, Nathan; Prince, Harry (2007). Problems in Contract Law: Cases and Materials (4th ed.). Aspen Publishers/Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. p. 659.

- ^ Public Trustee v Taylor [1978] VicRp 31, [1978] VR 289 (9 September 1977), Supreme Court (Vic, Australia).

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bix, Brian (2012). Contract Law: Rules, Theory, and Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 305

- ^ Misrepresentation Act 1967

- ^ Contract and Commercial Law Act 2017 (New Zealand)

- ^ Fuller, Lon; Eisenberg, Melvin (2001). Basic Contract Law (7th ed.). West Group. p. 388.

- ^ Fitzpatrick v Michel [1928] NSWStRp 19, (1928) 28 SR (NSW) 285 (2 April 1928), Supreme Court (NSW, Australia).

- ^ Bell v. Lever Brothers Ltd. [1931] ALL E.R. Rep. 1, [1932] A.C. 161

- ^ See also Svanosi v McNamara [1956] HCA 55, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Great Peace Shipping Ltd v Tsavliris Salvage (International) Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 1407, Court of Appeal (England and Wales).

- ^ Raffles v Wichelhaus (1864) 2 Hurl. & C. 906.

- ^ Smith v. Hughes [1871].

- ^ Taylor v Johnson [1983] HCA 5, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Lewis v Avery [1971] EWCA Civ 4, [1971] 3 All ER 907, Court of Appeal (England and Wales).

- ^ “Are you bound once you sign a contract?”. Legal Services Commission of South Australia. 2009-12-11. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ Black’s Law Dictionary (8th ed. 2004)

- ^ Johnson v Buttress [1936] HCA 41, (1936) 56 CLR 113 (17 March 1936), High Court (Australia).

- ^ See also Westmelton (Vic) Pty Ltd v Archer and Shulman [1982] VicRp 29, Supreme Court (Vic, Australia).

- ^ Odorizzi v. Bloomfield Sch. Dist., 246 Cal. App. 2d 123 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 1966)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd v Amadio [1983] HCA 14, (1983) 151 CLR 447 (12 May 1983), High Court (Australia).

- ^ See also Blomley v Ryan [1956] HCA 81, (1956) 99 CLR 362, High Court (Australia).

- ^ “Legislation – Australian Consumer Law”. consumerlaw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2018-09-14. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ^ Royal Bank of Canada v. Newell 147 D.L.R (4th) 268 (N.C.S.A.). 1996 case and 1997 appeal.

- ^ Tenet v. Doe, 544 U.S. 1 (2005).

- ^ Frustrated Contracts Act 1959 (Singapore)

- ^ Contract and Commercial Law Act 2017 (New Zealand), subpart 4

- ^ Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, Book Three, Chapter Four, Article 527

- ^ Benjamin’s Sale of Goods, 8th edition, para 8-092, quoted in High Court of Justice, Dunavant Enterprises Incorporated v Olympia Spinning & Weaving Mills Ltd [2011] EWHC 2028 (Comm), paragraph 29, delivered 29 July 2011, accessed 21 December 2023

- ^ Joanna Benjamin, Financial Law (2007, Oxford University Press), p264

- ^ Louise Gullifer, Goode and Gullifer on Legal Problems of Credit and Security, Sweet & Maxwell, 7th ed., 2017

- ^ “Annotated Civil Code of Quebec -English”. Lexum. Archived from the original on 2012-07-07. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ “NOMINATE CONTRACT, civil law”. law dictionary, a free online law dictionary search engine for definitions of law terminology & legal terms. law-dictionary.org. Archived from the original on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ “中华人民共和国民法典-全文”. Government of China. 2020-06-01. Archived from the original on 2020-09-07 – via State Council of People’s Republic of China.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, Book Three, Chapter Four, Article 509

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Article 35.

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Articles 41, 42.

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Articles 38, 39, 40.

- ^ Florian Faust, “Contractual Penalties in German Law”, (2015), 23, European Review of Private Law, Issue 3, pp. 285–296, [1]

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Article 25.

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Article 49, 64.

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Articles 74, 75, 76, 77.

- ^ United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Article 81.